Divergent and convergent thinking dates back to the mid 20th century, before smartphones were buzzing and laptops whirring... if you can imagine such a time. It was a period when our attention had more time to breathe and when we treated the creative and ideation process with more patience and respect. Innovation was less aggressive and competition less daunting. But divergent and convergent thinking, which has been pondered on and enriched by many thinkers and organizations ever since its apparition in the 1950s, is now more than ever a key to enabling successful collaborative innovation.

In this article, we’ll take you through a tour of the most notable divergence and convergence theories and go beyond the basics of how to implement different phases within your collaborative workshops. We’ll explore the depths of divergent and convergent thinking and examine how separating them out into different activities can foster the most powerful ideation processes for your workshops. That’s where truly original thinking can be unlocked.

Buckle up, it’s time to take off.

The history of divergent and convergent thinking

First up, a little history lesson.

The origins. JP Guildford and Alex Osborn.

The term divergent and convergent thinking was coined in 1950 by J.P. Guildford, an American psychologist who defined two fundamental stages of creative thinking within the human brain:

- Divergent thinking: used when an individual is faced with an open-ended task e.g. “How can a brick be used?”. From this perspective, divergent thinking is a problem solving mindset.

- Convergent thinking: when an individual needs to give one correct answer to a given question e.g. the answer to “Who won the World Cup in 2002?”

The theory was then most famously applied to Creative Problem Solving by founding member of ad agency BBDO (the ‘O’ in BBDO, to be precise), Alex Osborn. In his book “Applied Imagination”, first published in 1953, Osborn used a brilliant analogy to depict the different phases of divergent and convergent thinking and explain why it is so important to alternate these types of thinking. It goes something like this:

Suppose you’re the chairman of a committee to line up the main speaker for the opening dinner of your Community Chest campaign. The usual method would be to call your committee into a session to think up and knock down names. Perhaps a dozen possibilities would be considered.

But, suppose you hold two meetings - one to think up names, the other to select. For the first conference, each member would be asked to come with a list of his own. At this meeting you, as chairman, would read all these names aloud, without comment. Then you would ask for additional suggestions. The names brought in, plus those added at this session, would probably total around 100 instead of a dozen or so.

You could then send a list of the nominations to all the members, and ask each of them to come to the second conference with his first 10 choices marked. A composite list of preferences could be quickly drawn up in this meeting. The members could then discuss their pros and cons, and decide on the 10 most wanted speakers in the order of their desirability. The chances are that some of the names on this final list would never have been suggested in the usual form of conference. - Osborn, 1953

The point that Osborn was making clearly illustrates how the names on the final list would never have been thought of without separating divergent and convergent thinking i.e. conference one and conference two. To use Osborn’s analogy, they would have gone for the most conventional choice, selecting someone who was “top of the mind” to be the main speaker rather than going through the proper process of finding the best possible candidate.

Ideate and take decisions with Stormz!

Stormz is an easy-to-use facilitation platform for productive collaborative sessions: onboard participants in 30 seconds, nobody is left behind, everybody is enjoying the ride!

The maturation. Inclusion in CPS and Design Thinking processes.

Over time, thinkers and institutions have developed divergent and convergent theories to show the deeper impact into various areas. In particular, both Creative Problem Solving (CPS) and Design Thinking practitioners have embedded these theories in their processes.

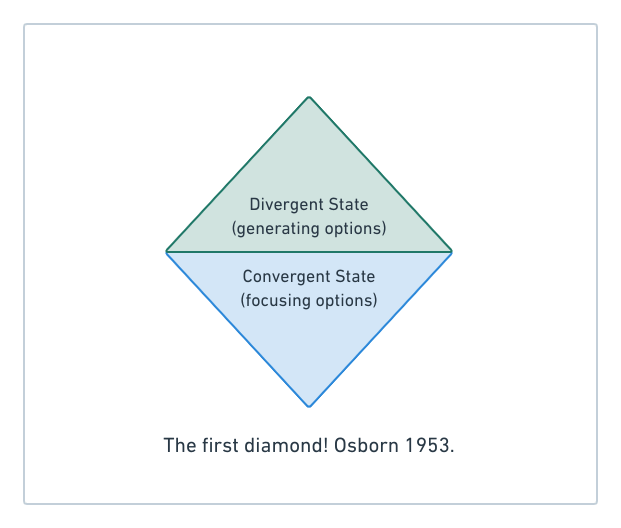

Osborn developed J.P. Guildford's divergent and convergent terminology into the original Osborn CPS process starting in 1953. This is the first process to show graphically that each step of the divergence/convergence process can be represented by a diamond <> (i.e. first going wide during the divergent phase, then narrowing during the convergent phase).

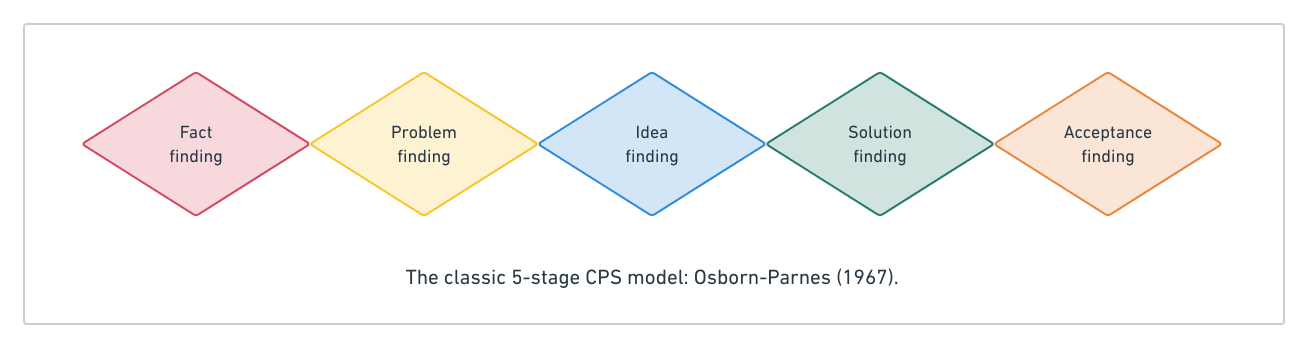

In 1967, Alex Osborn and his buddy Sid Parnes co-developed and enriched it into a five stage linear process <><><><><>.

Finally, the Creative Education Foundation (CEF) evolved the Osborn-Parnes model to account for a less strict linear approach with a basic structure consisting of four non-linear stages and a total of six explicit process steps <><><><><><>.

Four, five or even nine steps: the models can differ but the important thing is that each single step without exception alternates divergent and convergent thinking.

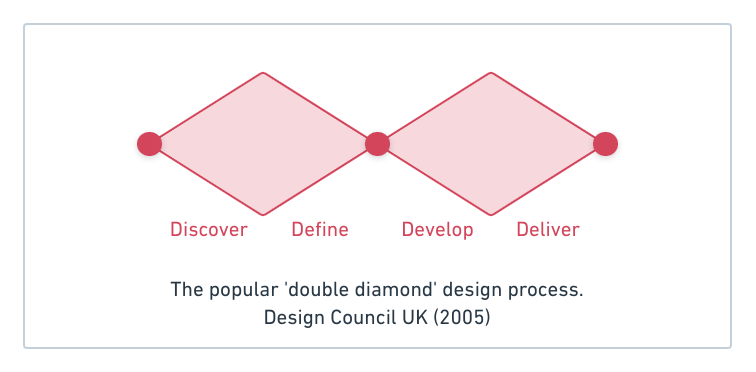

Much later, in 2004 the design thinking community kind of reinvented the wheel when the UK Design Council developed the Design Process Model, the “first” (in the design thinking world) to implement a double diamond <><>. It was a popular success and this universally accessible visualization of a design thinking process has become an accepted part of design language, used and referenced worldwide today.

What is divergent and convergent thinking?

The time has come to really break down what divergent and convergent thinking stands for, particularly in the context of facilitation and creative problem solving.

All creative thinking follows a pattern, a specific rhythmic beat within all of us, expanding and contracting like the motions of a heart or the coming and goings of a tide. In a microcosm, this allows us to ideate as wide as possible before narrowing down our thought process to reach a decision. This process can also take place within seconds in our daily lives. Those two opposite and complementary strands of creative thinking are what we call divergent and convergent mindsets.

< What is divergent thinking?

Divergent thinking is the act of exploring all possibilities. It’s the notion of going wide on possible ideas without the restraint of pros and cons. In too many creative workshops, free-thinking ideas are voiced but immediately disregarded or dismissed due to them being impractical, unrealistic, or out of step with the end goal. When participants are engaged in divergent thinking, it should be a dreamy, playful and fun-filled experience where no idea is a bad idea and where all ideas have the potential of becoming solutions.

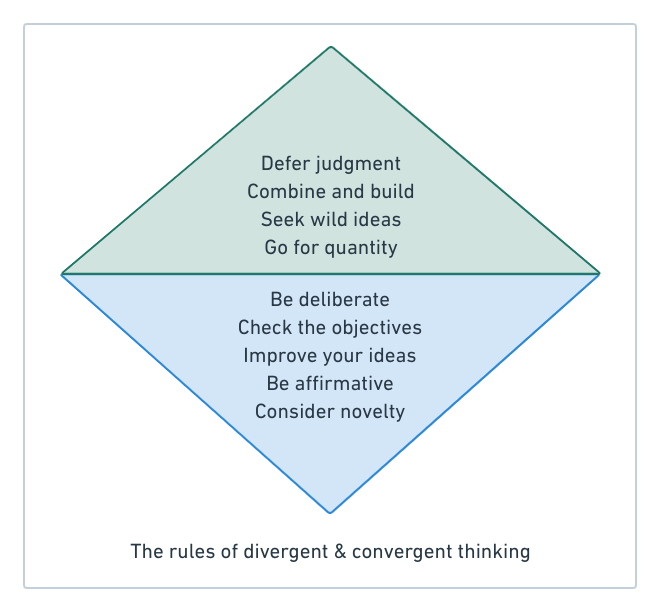

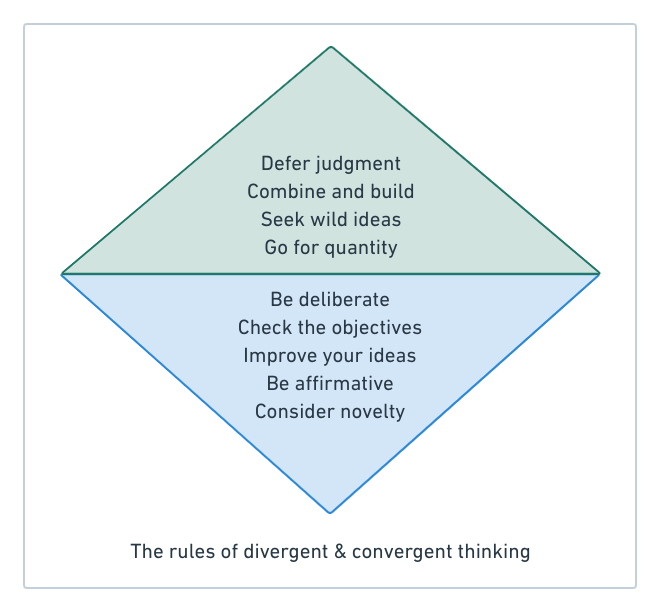

These are the key rules of divergent thinking, as outlined in the Creative Education Foundation’s dedicated guide:

- Defer judgment

- Combine and build

- Seek wild ideas

- Go for quantity

Divergent thinking is the act of starting with a blank canvas and splattering any colour, any shape, any line or any texture without worrying about the end-result. As Dorte Nielsen and Sarah Thuber put it in their brilliant book “The Secret of the Highly Creative Thinker”, divergent thinking is like staring at an open refrigerator and considering all the marvelous combinations you could make for lunch. Like a wonderful hamburger with patties, lettuce, tomatoes and nutella on top, served by a unicorn wearing pyjamas? These are the kinds of ideas that should be encouraged to blossom in a divergent mindset environment.

> What is convergent thinking?

In terms of problem-solving and decision-making, divergent thinking is evidently not enough. Enter the convergent mindset, the act of refining your divergent ideas into tangible possibilities that can be acted upon. It’s the state of mind where reason and rational thinking get in full swing and is only possible - or desirable - once you know that the creative, go-crazy type of thinking has been done. It’s now time to assess, evaluate and enrich these original ideas to turn them into real solutions.

These are the key rules of convergent thinking:

- Be deliberate

- Check the objectives

- Improve your ideas

- Be affirmative

- Consider novelty

Convergent thinking is bringing reality to the party, like getting your checklist of pros and cons and marking them against the ideas that came out of your divergent phase. That list of ideas will quickly be whittled down to those that are realistic and feasible. The trick to convergent thinking is to be deliberate, yet considerate within the selection process. In other words: now is the time to get rid of ideas that are way off target, but be careful not to throw away novel ideas that could be worth a shot. To come back to Dorte's and Sarah's culinary metaphor, it’s like taking the bread, meat, tomatoes and lettuce for your burger, losing the nutella but considering that mustard-mayonnaise might bring an interesting and original twist...

Why separating divergent and convergent thinking is key?

While many are able to understand how divergent and convergent thinking actually works, too many workshops still fail to use them in a harmonious way. This requires to grasp the one fundamental aspect: used within the same overall cycle of ideation, divergence and convergence must be separated in two distinct phases.

Think about it: could one individual - let alone a team - really diverge and converge at the same time? Go crazy with new ideas while simultaneously voting on the best one? This lack of separation leads to workshops where ideas aren’t given an equal chance, where they’re rushed out, too quickly agreed upon or on the contrary too rapidly dismissed before they have time to reach their full potential. It leads to frustrated participants, unrealistically expected to think in both a divergent and convergent way simultaneously. Now you get it: for divergent and convergent thinking to really work together in unlocking the most powerful and original ideas, the two states of mind need to be in harmony and distinctively apart. The root of our challenge as facilitators is to separate divergent and convergent elements within the framework of a seamless design and engaging activities.

As Dorte and Sarah intelligently phrased it, convergent and divergent cycles are the heartbeat of creativity, and separating the phases helps participants reach truly original ideas as it enables them to make rare connections beyond the realms of regular problem solving. For that, the careful balance of each phase in the cycle should be considered: too much time in a divergent mode generates lots of ideas but no action; too much time spent in a convergent mode may result in better options being left undiscovered.

Once this balance is found, divergent and convergent cycles can be used for many different outputs. Most people have been exposed to the concepts of divergence and convergence with the all-mighty brainstorm, which in itself is not enough, and should always be followed by critical thinking and evaluation (convergence). This over-popularity of the brainstorm - and the wrong ways many workshops apply it - has led to divergence and convergence methods being used for idea-finding only. But that’s not the case: problem finding, fact finding, experiment planning, etc. Comprehensive workshops should imperatively look to explore these avenues.

Going Further. Clustering, the missing link between both phases?

In 2007, Tassoul and Bujis argue that "clustering is neither a form of diverging (you do not add new ideas) nor a form of converging (you do not discard any ideas)"; so they proposed adding a cluster step in between each divergence/convergence cycle, the perfect segue between the two mindsets.

And they are not the only ones, there are many variations and alternatives out there that have been put forward by academics and practitioners. In the end, just keep in mind that each phase of your workshop should follow the basic principle of alternating a divergent phase with a convergent phase. One way or the other, stick to it!

Learn facilitation with our tips and tricks!

Subscribe to our free newsletter for facilitators.

A tip. Using < and > to create the visual signature of your workshop

You can visually show the alternance of divergence and convergence steps with > and < . Do it when you design your workshop: it is a powerful visual signature of how your workshop is implementing divergence and convergence:

< >: the basic diamond.< > < >: the double diamond.< < <: several successive step of divergence, frequent in a creativity workshop, using different creativity techniques to encourage the participants to generate more ideas.> > >: several successive steps of convergence, when there are a lot of ideas, you can use different convergence mechanisms to shortlist ideas and select the best one.< > < > << >>: a balanced workshop with a succession of div/con phases.< > <: don't do that! There are exceptions, but it is generally a bad idea to end a workshop with a divergence activity.

Note: as mentioned earlier, some consider that clustering or any other exploring or sense-making activity is neither convergence or divergence. If it is the case, you can use the = symbol. Your workshop signature will turn into something like that: < = > .

Example of divergent/convergent workshop design

Now it's time to get specific and see how we can apply the concept of divergence/convergence in a real workshop. Of course, we will use Stormz to design the workshop, but the principles would be the same with Post-it notes and flip charts.

Exploring the vision is the first step in the Clarify stage of the Osborn-Parnes Creative Problem Solving process. This is where the participants will co-create a vision of success. It’s the perfect workshop to demonstrate how divergent and convergent steps work together. It is also an example on how divergent and convergent thinking can be used for something else than brainstorming solutions.

The workshop is articulated around two phases:

First, a divergent phase. Here the objective is to generate as many “wish” statements as possible.

- Step 1. > Silent brainstorming, to get unbiased ideas.

- Step 2. > Open brainstorming, for participants to build on others' ideas.

Then, guess what? A convergent phase.

- Step 3 < A $100 budget game, to shortlist the most relevant wishes.

- Step 4 < The 3 "I"s technique (Importance, Influence, Imagination) to select the one.

In a nutshell, this is what we do: < < > > (2 successive steps of divergence, followed by 2 successive steps of convergence). Of course, the step system in Stormz allows us to set up these multiple steps very easily.

Use Stormz to facilitate divergence and convergence

Stormz is the perfect digital tool to run CPS workshops. If you are curious, you can learn from any of our CPS templates.

A final word?

This is one of many examples of how the combination of multiple divergent and convergent steps can lead to powerful workshops - a place where expansive thinking can blossom and flower into life, without being restrained by limiting practicalities, where ideas can reach their full potential.

Stay brave and determined as you venture into the wonderful world of divergent/convergent powered workshops, and do not get discouraged by the fact that the ideas you’ll end up with probably won’t be those you expected at first. On the contrary: that’s the greatest beauty of it, isn’t it?

Sources

- Nielsen, D and Thurber, S (2016) The Secret of the Highly Creative Thinker: How To Make Connections Others Don't

- Osborn, A. F. (1953) Applied Imagination: Principles and Procedures of Creative Problem-Solving,

- Parnes, S.J. (1967) Creative Behavior Guidebook.

- Tassoul, M. and Buijs, J. (2007) Clustering: An Essential Step from Diverging to Converging. Creativity and Innovation Management.